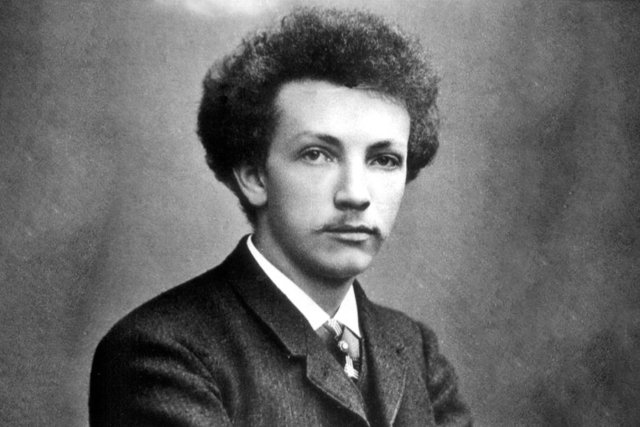

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss enjoyed a long and profound relationship with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. His prolific output – encompassing symphonic poems, songs, and operas – has graced its programmes countless times, and Strauss himself conducted the Orchestra an impressive 41 times.

Virtuoso orchestrator

Strauss rose to prominence in the late 19th century with his masterfully orchestrated symphonic poems. Initially, he aligned with the progressive camp of innovators such as Wagner and Liszt. Strauss’s music was adventurous, colourful, and often controversial. It had the power to express everything from folk tales to philosophical treatises, from a mountain hike to a marital dispute. He famously quipped that he could depict in music a glass of beer so accurately that you would be able to tell “whether it is a Pilsner or Kumbacher!”.

Masterpieces of tomorrow

At their premiere, Strauss’s ambitious symphonic poems were often considered difficult, heavy and modern. The fact that we are now accustomed to them and enjoy his music so much is largely thanks to conductors like Willem Kes and Willem Mengelberg, the first chief conductors of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, who always held fast to their artistic vision. Their perseverance also paved the way for other composers once unloved, such as Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner. It underscores the vital importance of performing contemporary music, even when it goes against current sensibility. As future chief conductor Klaus Mäkelä says, “That too is an important tradition of the Concertgebouw Orchestra: playing the masterpieces of tomorrow.”

The early steps

During one of the first concerts of the Concertgebouw Orchestra on 22 November 1888, chief conductor Willem Kes programmed the Horn Concerto by the young Strauss. In the same year, Strauss completed his groundbreaking symphonic poem Don Juan, which cemented his reputation. Kes conducted Don Juan thirteen times from 1891, with the last performance in 1895, the year Willem Mengelberg succeeded him. Mengelberg proved to be an even more enthusiastic champion, deepening the bond with Strauss.

Mengelberg – only 24 years old when he took the podium! – was a perfectionist with grand ambitions. In a short time, he moulded the Amsterdam orchestra into an internationally renowned ensemble. This was achieved through his notoriously strict disciplinary measures, but also by cultivating close ties with celebrated composers, even those who were not yet widely popular with the public, such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss.

Strauss conducts the Orchestra

In September 1897, Mengelberg fell ill, prompting the orchestra’s board to seek a replacement. They aimed high, inviting both Arthur Nikisch and Richard Strauss. Strauss accepted, coming to the Van Baerlestraat to conduct the Concertgebouw Orchestra on 7 October 1897, in the Dutch premiere of his Tod und Verklärung.

This symphonic poem, depicting an artist’s death and inspired by the philosophical writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, was a challenging listen for the Amsterdam audience. But Mengelberg knew what was good for them and was to programme it many more times. Strauss’s name was immortalised on one of the cartouches adorning the Main Hall (at the expense of Charles Gounod, who later, incidentally, regained his place in the hall of fame).

The dedication: Ein Heldenleben

Strauss, in turn, was deeply impressed by the newly created Concertgebouw Orchestra. “The orchestra is truly splendid, full of youthful freshness and spirit, and excellently prepared, making it a true pleasure to conduct,” he wrote to his wife, the soprano Pauline de Ahna.

In the following year, Strauss returned, conducting both Tod und Verklärung and his more recent Also sprach Zarathustra. Again, he was delighted with the Orchestra and Mengelberg’s diligent preparation. So much so that he dedicated his next major symphonic poem, Ein Heldenleben, “to Willem Mengelberg and his Concertgebouw Orchestra.” On 26 October 1899, a few months after its Frankfurt premiere, this grandly conceived work (featuring, for example, eight horns and five trumpets) reverberated within the walls of The Concertgebouw.

Criticism and acceptance

It was a sensation, and not entirely in the positive sense. A storm of criticism erupted. How dared this windbag portray himself as the great hero in an orchestral work of Wagnerian proportions? And in E-flat major, no less – the heroic key of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony. Ein Heldenleben was dismissed by critics as a pompous excess of the Wilhelminian era in Germany (where Emperor Wilhelm II had been an autocrat since he dismissed Bismarck in 1890).

Gradually, the public came to understand that self-glorification was only one aspect of Ein Heldenleben. Irony and self-deprecating humour also reside within the music. Strauss takes the listener on a captivating journey that moves from one spectacularly orchestrated situation to the next. At the end, a profoundly moving duet unfolds between the solo horn (the composer) and the solo violin (his wife).

Intensification and embrace

Undaunted, Mengelberg continued his Strauss campaign. Exactly one month after the premiere of Ein Heldenleben, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche was added to the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s repertoire. The Orchestra also repeatedly invited Strauss back as conductor. In 1903, Strauss even conducted three programmes exclusively featuring his own works. Subsequently, under the baton of both the composer and Mengelberg, the Orchestra performed these pieces multiple times during a Richard Strauss festival in London. Gradually, Strauss’s music was being embraced by the public. Ein Heldenleben eventually became a crown jewel of the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Romanticist

Meanwhile, Strauss ventured into opera with at least equal success – and occasional scandal. The last time Strauss conducted the Orchestra was in 1934. On 29 November and 1 December, he conducted his opera Arabella, with twelve soloists and choir, and on Sunday afternoon 2 December, he led a “Richard Strauss Festival” featuring the symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra, various lieder, and excerpts from his early opera Salome.

Strauss never fully embraced explicitly modernist trends and over the course of the 20th century he was increasingly seen as a relic of the past. His failure to resist the Nazi regime did not help his reputation. After the war, his music explicitly looked back to 19th-century Romanticism. A transition from avant-garde to traditionalist. He passed away in 1949. However, his music – sometimes innovative, sometimes old-fashioned, but always masterfully crafted and never dull – continues to be a frequent guest on the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s stands.