Fri, Oct 1, 2021

It all started when his grandmother gave him a violin. Now, too, the special instrument the Concertgebouw Orchestra's leader Vesko Eschkenazy plays is of great significance to his life and career.

By Marije Bosnak - This article previously appeared in the 2021 Annual Report of the Foundation Concertgebouworkest.

Warmth and applause

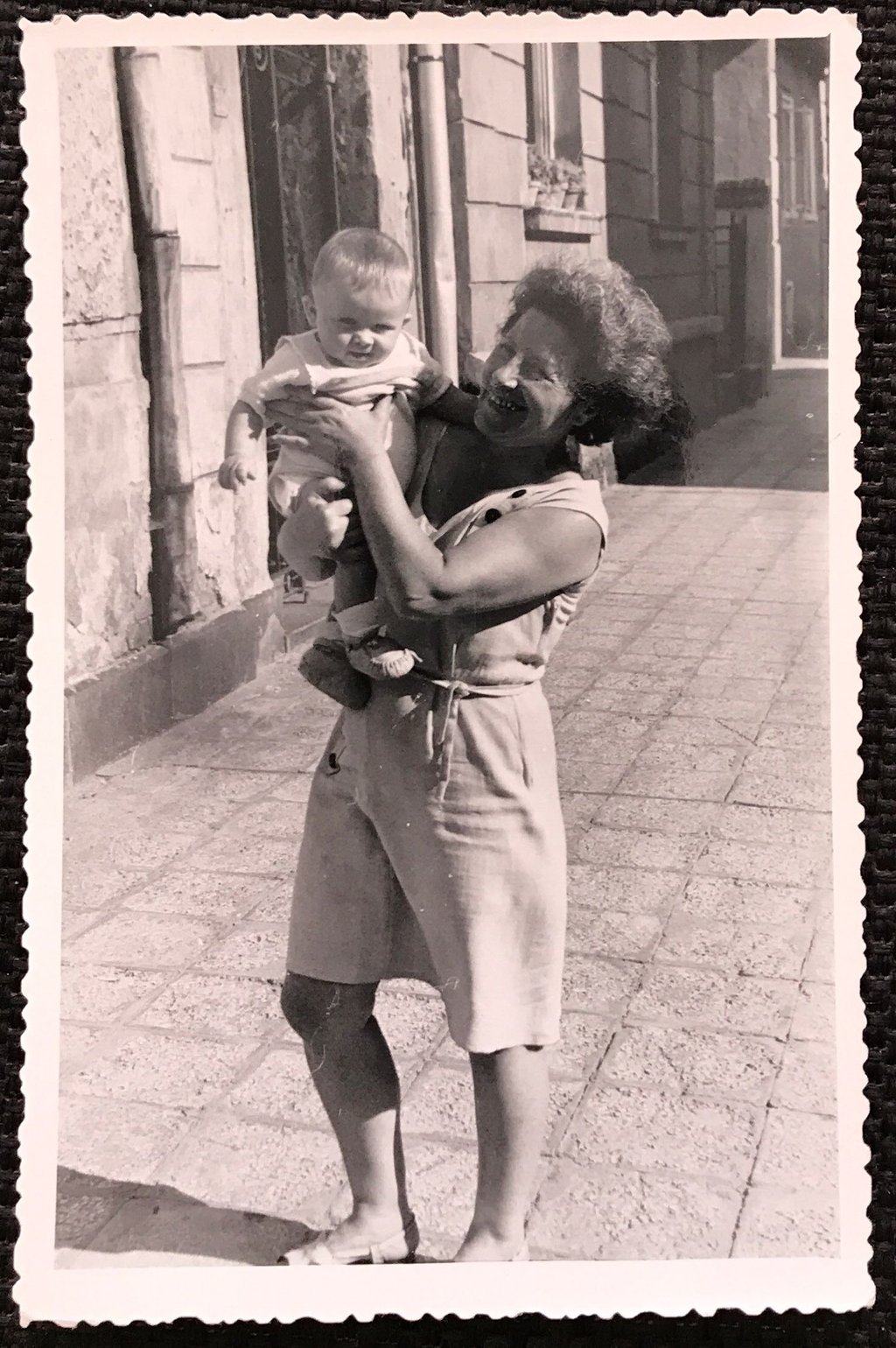

‘Even as a little boy, I was already playing the violin, and the first people I ever performed for were members of my family. My grandmother in particular played a crucial role in my development as a young violinist. I grew up in a flat in Sofia with her and my parents, as was quite normal. My grandmother was a very sweet person. She wasn’t a musician, but adored music and gave all the children in the family a violin. So from an early age, my brother, my two cousins and I would play at family gatherings.

‘My first concert? I remember a birthday party at our house. There was talk, laughter, food – we had a big family – and at one point, someone asked, “Vesko, why don’t you play something for us?” So I took my violin and bow out of the case and played what I had just learned at the music school. How they all applauded! I remember it so well. That was part of making music. I had no sense of pride or anything like that, but for me, playing the violin has definitely always been connected with my family’s enthusiasm.’

I had no sense of pride or anything like that, but for me, playing the violin has definitely always been connected with my family’s enthusiasm.

Attention and discipline

‘The violin my grandmother gave me was the beginning. But the attention she gave me was so meaningful, too, and supported my violin playing. She gently taught me what discipline is – that I had to do something for the music, that I had to work and improve myself. After school, she would always say, “Go and practise for just two hours.”

Similarly, my music teachers at school supported me as well. They would ask questions like, What do you want to do when you grow up? Do you want to improve? What can you do to improve? As a child, I didn’t stop to consider the complicated process and all the hours that lead up to performing onstage. In fact, it was only much later that I also discovered the psychological difference between practising and performing – the state of heightened tension that goes into ensuring that what you’ve practised sounds the best it can sound in performance.’

Love and inspiration

‘Those times I would play for my family and the warmth and love around me had a huge influence on my career. And since making music is connected with all those precious memories, playing the violin is really the most beautiful thing I’m capable of doing. And that’s so important as a musician: you really have to love this profession – otherwise you won’t make it. You have to be in love with making music.

‘Those childhood memories will stay with me forever as a source of inspiration. You need those, too, in this profession. That’s how I deal with nerves before a concert. The memories are a foundation on which I can rely over and over; they evoke in me the sense that making music is wonderful – that I’m not just working. Performing music should never become “just work” or routine. Every evening, you have to find the inspiration to play as if it were the very first time.

‘Of course, that’s true of many professions, too. It’s important to love the work you do and stay inspired. But we connect with music in order to convey emotions to the audience. And that’s possible only if you have a love of the profession and an inner source of inspiration.’

A broken circle

‘It’s hard to talk about the support I normally feel from the audience when we’re in the middle of a pandemic. It may not be true for everyone, but I miss it all. The hall feels so different without an audience. The atmosphere. I miss the contact – in fact, I’ve never been so intensely aware of it before.

‘On the face of it, objectively speaking, we – the musicians onstage and the audience in the hall – don’t necessarily have much to do with each other. Obviously, we can perform without an audience. But when I see the people and feel they’ve come to experience something beautiful that we’ll be performing for them, a circle is created. Without an audience, the circle is broken. That’s painful – I mean, why are we making music in the first place? Those moments when I’m aware of 2,200 people in the hall when we’re playing very soft passages in a Mahler symphony are truly unforgettable. The subdued moments between the notes. That silence. That’s the magic of making music.’

Inconceivable

‘For me, the very first thing the words “support” and “commitment” call to mind is the violin which I’ve been allowed to play for the last twenty years as leader of the orchestra and which is on loan to me from private individuals through the orchestra’s foundation.* Just the idea that people exist who make that possible – it’s such a noble act, inconceivably noble. You own such a valuable instrument, and you turn around and let someone else play it. I really am one of the very few lucky people in the world. I can’t emphasise enough how much this instrument has contributed to my own development as a musician.’

*Vesko plays the ‘ex-Silverstein’ Guarneri del Gesù built in 1742. The instrument is owned by a private patron and is specially on loan to him from the Foundation Concertgebouw Orchestra.