Gustav Mahler

The Concertgebouw Orchestra is globally celebrated for its Mahler interpretations, a tradition that began in 1903 when Mahler himself came to Amsterdam to conduct his own work, notably the monumental Symphony No. 3 for orchestra, women’s choir, children’s choir, and mezzo-soprano.

Mahler and the Concertgebouw Orchestra

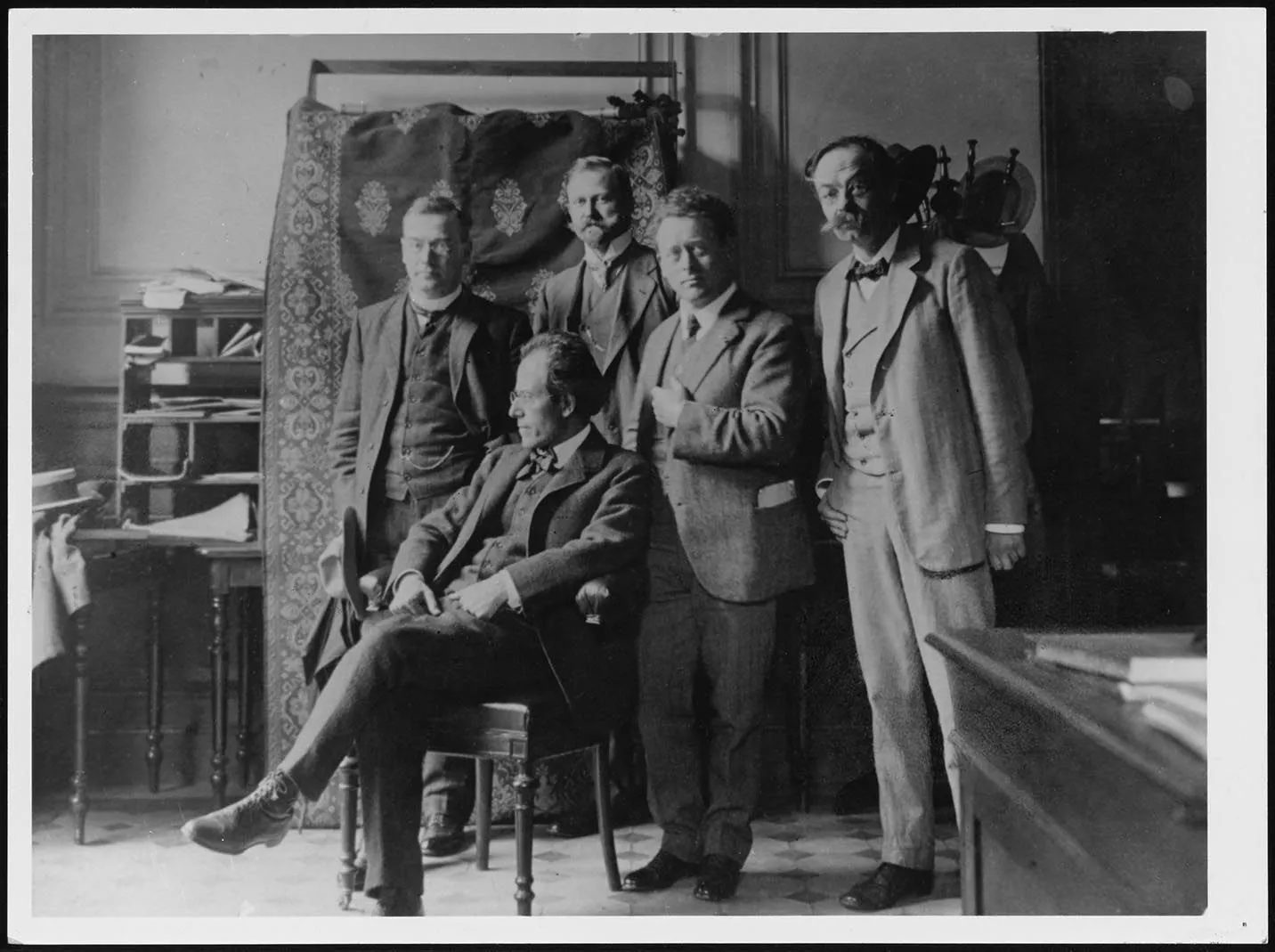

This initial visit marked the beginning of a deep collaboration between Mahler and the Concertgebouw Orchestra and a unique, enduring tradition. This was largely the achievement of Willem Mengelberg, the orchestra’s chief conductor from 1895. Mengelberg, even in his youth, had a sharp nose for interesting contemporary composers. With tireless missionary zeal, he championed Mahler’s works – initially unknown and not very popular – to the Amsterdam public, and he succeeded. Subsequent chief conductors, including Eduard van Beinum, Bernard Haitink, and Riccardo Chailly, have each added inspiring new chapters to this legacy. Future chief conductor Klaus Mäkelä is ready to seamlessly adopt the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s rich Mahler tradition.

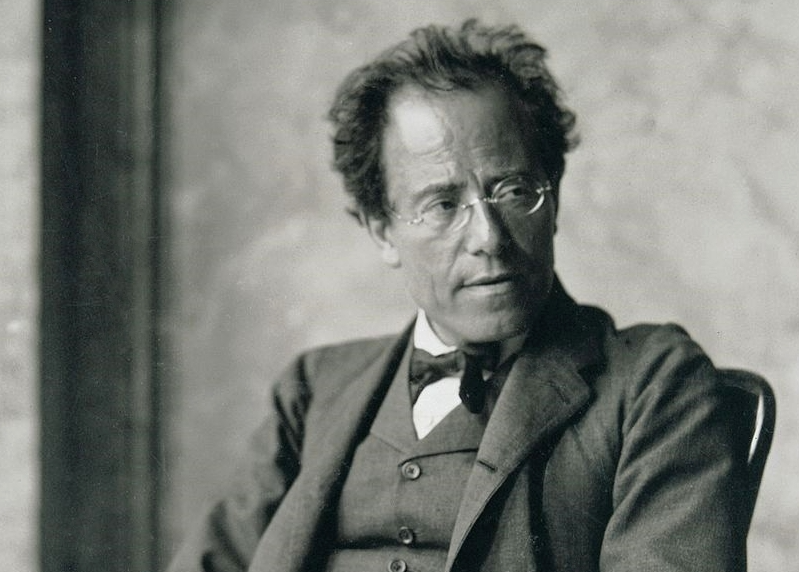

Gustav Mahler’s unique path

Gustav Mahler came from a Jewish family and was born and raised in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). As a composer he was too progressive for the general public; he was known primarily as a conductor. After a position in Hamburg, he became the artistic director of the Vienna Hofoper in 1897. Due to the prevailing antisemitic climate, Mahler was compelled to convert to Catholicism. Later, again because of antisemitism, he emigrated to America, where he became chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

With his grand symphonies and orchestral songs, Mahler stands at the end of Romanticism and the beginning of 21st-century modernism. He delved into profound philosophical questions and intense self-examination – coinciding with the nascent era of psychoanalysis – translating these into compelling musical expression. He steadfastly forged his own, unique path.

“A symphony must be like the world”

In the second half of the 19th century, a symphonist would typically choose between two paths: “absolute music”, cleaving to the classical forms of Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruckner, or the newer approach of Liszt, Wagner, and Richard Strauss, where musical form was dictated by a literary or philosophical “programme.” Mahler embraced neither exclusively, or perhaps both. His Symphony No. 1 comprises four classical movements but is replete with quotations and extra-musical allusions, such as to Jean Paul’s novel Titan. Mahler’s unique, transparent orchestration is already evident here.

Mahler’s famous dictum, “A symphony must be like the world; it must embrace everything,” encapsulates his vision. His existential Symphony No. 2 fittingly spans an hour and a half. Its final movement is an orchestral song – the integration of songs into symphonies was a Mahler signature. In the six-movement Symphony No. 3 for orchestra, solo alto, women’s choir, and children’s choir, classical forms are barely discernible. It was this symphony, performed in Krefeld in 1902, that caught the attention of Willem Mengelberg.

Mengelberg invites Mahler

Mengelberg was immediately struck by the fascinating power emanating from the composer-conductor: “In his interpretation, in his technical handling of the orchestra, in his way of phrasing and building, I found that which to me – as a young conductor – seemed ideal. When I then [...] personally became acquainted with him, I was deeply moved by his music.”

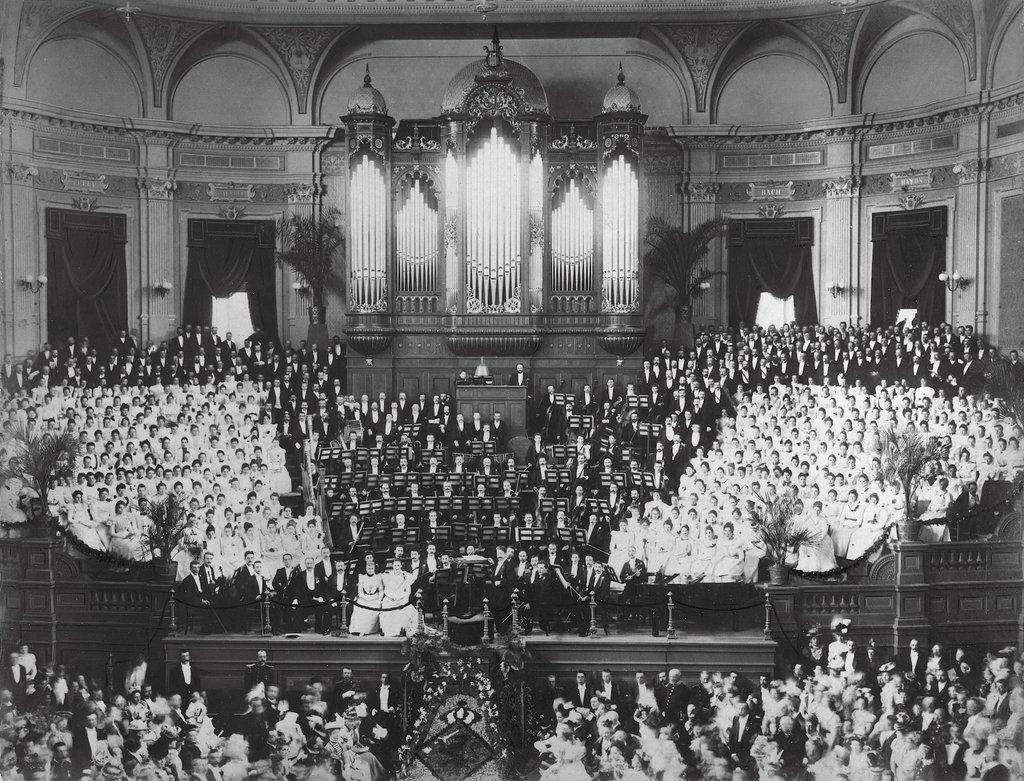

Mahler’s compositions were often deemed too long and complex by most music enthusiasts. However, Willem Mengelberg was determined to elevate the musical tastes of the Amsterdam audience. He persuaded Mahler to conduct his Symphony No. 3 in Amsterdam in 1903. Given the complexity of the work and Mahler’s reputation for being temperamental, Mengelberg prepared the Orchestra thoroughly. Mahler was delighted, and rehearsals under his direction ran smoothly. He wrote to his wife Alma: “Yesterday’s dress rehearsal was splendid. Two hundred schoolboys led by their teachers (six of them) roared the bimm, bamm and there was a magnificent women’s choir of one hundred and fifty voices! Orchestra splendid! Much better than in Krefeld. The violins as beautiful as in Vienna.”

A tradition is born

Reactions were mixed. But Mahler was mainly pleased and surprised by the audience’s adventurous receptiveness. A day later, he wrote to Alma: “A bit more about last night. It was wonderful. At first, people were a bit uncomfortable, but after each movement, they grew warmer, and when the alto solo began, they slowly but surely completely gave in. After the final chord, there was applause and cheering that was really quite impressive. Everyone told me that they couldn’t remember such a success ever before.”

Mahler returned to Amsterdam in 1904, 1906, and 1909. Tragically, he succumbed to his long-standing heart condition in 1911; otherwise, he would undoubtedly have visited Amsterdam many more times. On 9 March 1912, the Concertgebouw Orchestra performed the Dutch premiere of the colossal Symphony No. 8, while at the same moment, the Dutch consul in Vienna laid a wreath on Mahler’s grave, “as a token of the love, reverence, and gratitude of his Amsterdam friends”.

In 1920, artistic director Rudolf Mengelberg organised a Mahler Festival to commemorate his cousin Willem’s 25th conducting jubilee. A few years later, Willem Mengelberg received permission from Alma, Mahler’s widow, to orchestrate and perform two movements of the unfinished Symphony No. 10.

During World War II, Mahler’s music couldn’t be played because of the occupiers’ ban on performance of music by Jewish composers, notwithstanding protests from musicians, the public, and Mengelberg himself.

Legendary recordings and festivals

After the war, Mengelberg was banned from conducting due to his problematic stance during the occupation. Mahler’s works remained in the Concertgebouw Orchestra repertoire,

however, and grew increasingly popular with the Dutch public. Recordings of the symphonies under Mengelberg and Eduard van Beinum attained a legendary status. The same is true for the Mahler recordings and internationally broadcast Christmas Matinees (from the 1970s onward) under the direction of Bernard Haitink.